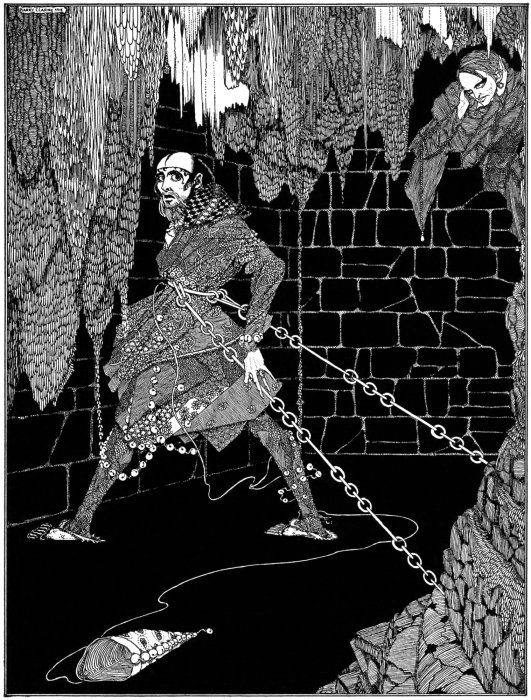

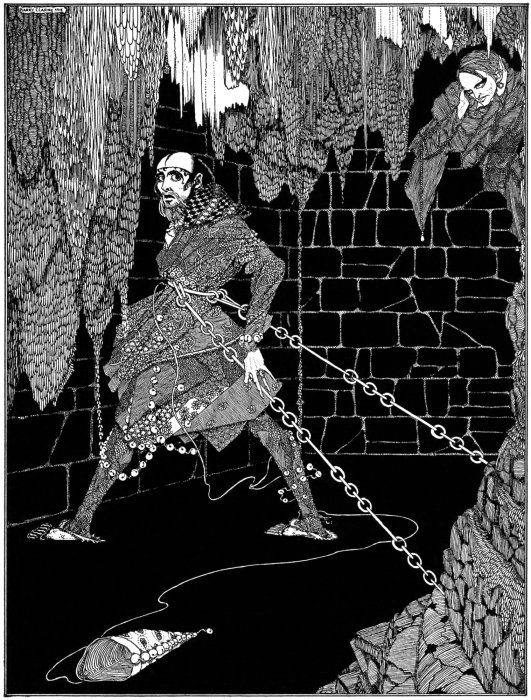

An illustration of poor Fortunato that appeared with the 1919 publication of Poe's short story.

Last month, my wife and I went as Poe characters to a Halloween party — she as the Raven and myself as Fortunato, the poor sap who gets bricked up in the catacombs in “The Cask of Amontillado.”

Before the big night, I reread the source material to make sure I hadn’t omitted anything from the costume. After all, it’d been a couple decades since I’d last taken a look at “Cask.”

Turns out, I should reread Poe more often. While I vividly remembered the story’s creepy atmosphere and swelling sense of dread, I didn’t recall “The Cask of Amontillado” having such sharp dialogue.

As writers, we sometimes fall into the trap of writing dialogue that’s too transparent, too truthful to the characters’ real motives. For one, it’s tricky to capture the subtle obfuscation we engage in during everyday conversation. Also, we tend to underestimate readers and assume they’ll take untruthful dialogue at face value.

In “Cask,” neither of Poe’s characters speaks the truth. They verbally mislead each other (or at least attempt to) from the opening to the point when Fortunato’s fate is literally sealed. And it works because Poe, master that he is, gives us cues to guess what lurks beneath the characters’ lies, boasts and half truths.

It’s a lesson any writer could learn from.

The nobleman Fortunato presents himself as an expert in wines and spirits, yet Poe provides us enough hints to show he’s simply a blowhard. Early on, for example, he derides another purported connoisseur for being unable to “distinguish Sherry from Amontillado.” Amontillado is, in fact, a type of Sherry.

Montresor, the revenge-minded rival who bricks up Fortunato, guides his victim to doom by appealing to his ego and falsely extolling his expertise. Even though Fortunato should pick up on countless hints something ghastly lies in store, he can’t resist the lure of Montresor’s flattery.

When Fortunato raises a toast, Montresor’s response drips with both irony and menace. It’s clear his response, like so much of the story’s best dialogue, has a dreadful double meaning.

“Thank you, my friend. I drink to the dead who lie sleeping around us.”

“And I, Fortunato — I drink to your long life.”

Bravo, Mr. Poe! I raise my Fortunato cocktail to the long life of your work.

This installment’s “Cask”-inspired mixed drink is a twist on the Teenage Riot, originally devised by New York bartender Tonia Guffey. In honor of poor Fortunato, I increased the amount of Amontillado and substituted the bitter and citrusy Italian aperitif Campari for the original’s Cynar, another Italian liqueur.

While the Riot’s Cynar imparts a nice herbaceous quality, the Campari used here plays against the Amontillado’s raisiny sweetness with bitter orange-peel notes. (Isn’t revenge supposed to be bittersweet?) The sherry and Campari, combined with the rye, create the sensation of scarfing down a really boozy slice of fruitcake.

The Fortunato

1 1/2 oz Rye Whiskey

1 1/4 oz Campari

3/4 oz Lustau Dry Amontillado Sherry

1/2 oz Dry Vermouth

Stir with ice and strain into a coupe glass. Garnish with a slice of orange rind.