All art is political.

Whether or not the artist intends it to be taken that way is a moot point. Others will assign politics to the work, even if the creator doesn’t. Witness, for example, the fascinating documentary Room 237, in which Stanley Kubrick obsessives assign subtext and symbolism to The Shining the director likely never intended.

As a horror author, I wince when people characterize the genre as being inherently conservative (a notion also frequently applied to fantasy). Horror stories, some critics argue, are essentially about stopping forces from changing the status quo — putting the genie back in the bottle, so to speak. What’s more, the genre also has a long and unfortunate tradition of making the other a source of fear.

Author Paul Tremblay clearly struggles with the same unease about that categorization. His recent essay in Nightmare Magazine, “The H Word: The Politics of Horror,” presents an eloquent argument that horror, if well-executed, deserves a progressive interpretation rather than a conservative one.

While horror protagonists’ objectives are almost always to bring a return of the status quo, Tremblay points out that horror’s quest to make us uncomfortable necessitates that characters and readers confront truths that will permanently change them. This shift in outlook dispels the very conservative fallacy that things were different in the “good old days.”

“Not only are (the good old days) gone and never coming back, they never existed in the first place,” Tremblay writes. “That’s the horror of existence. Change happens whether you want it to or not.”

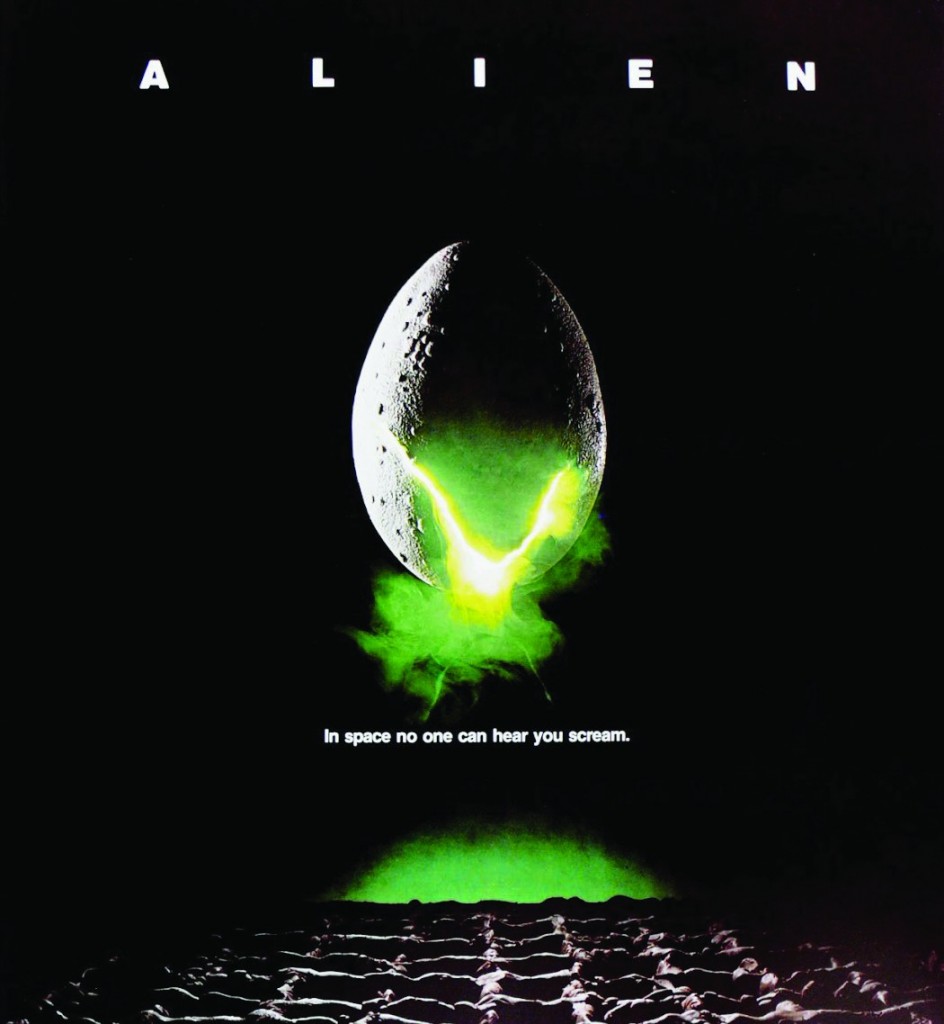

By way of example, he points to Alien, the haunted-house-in-space installment of that film franchise. The movie ends with Ripley floating alone in a vast and uncaring cosmos, lucky to have escaped with her life. By contrast, in Aliens, more of an action flick than its predecessor, Ripley settles into hibernation with her surrogate family of Newt and Hicks, telling the girl they’re safe to dream again.

I maintain that perspective-altering aspect of horror is what appealed to the creators of the ’70s and ’80s who unleashed an innovative and bloody wave of fiction and film that commented on the Vietnam War, racism, urban isolation, AIDS and the military-industrial complex from a left-of-center perspective.

In his documentary Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film, Mick Garris points out that George Romero, David Cronenberg, Clive Barker and Stephen King all aim to turn an oppressive status quo on its head. “It’s the people who repress them who are the ones you have to look out for,” Garris argues.

Indeed, the conservative politics of division and discrimination can be an effective tool for creating and sustaining the isolation needed to make a horror story work. Consider the racism in Joe R. Lansdale’s The Bottoms and the fear of the gay title character in Lee Thomas’ The German. Only after the protagonists in both books are able to overcome their fear of the other are they able to effectively fight off a larger evil.

Is this to say horror always has a progressive bent? Certainly not. Slasher films and some other horror subgenres are conservative as the “700 Club.” In these works, teens who explore sexuality are punished in gruesome ways and only characters’ faith in a Christian higher power can rout supernatural evil.

To my mind, horror is neither inherently progressive or conservative. The genre’s themes and variations, the intent of its creators and the perspectives of its observers are simply too broad for that to be the case.

But Tremblay is fundamentally correct: the progressive notion is frequently what makes a horror story stick with us. The best such work terrifies us because it alters our outlook on the way the universe works and shows us change — whether or not we’re ready to face it — is inevitable.